Introduction to Indian Judiciary

The Indian democracy rests upon the federal system of division of powers. The authority of making laws and executing them lies in the hands of the legislature and the executive. However, the sole authority of interpretation of laws and protection of citizen’s interests is on the shoulders of the judiciary. Hence it is called, the “custodian of the constitution”, meaning the guardian and interpreter. The judiciary has the final say in constitutional validity and legal matters.

The Indian judiciary is unique in its feature of judicial review, wherein it takes cognizance of a law rolled by the legislature and decides its validity under the constitution. The judiciary was envisaged as the bastion of rights and justice, and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar described it as ‘one single integrated judiciary having jurisdiction and providing remedies in all cases arising under the constitutional law, criminal law or the civil law, essential to maintain the unity of the country.’

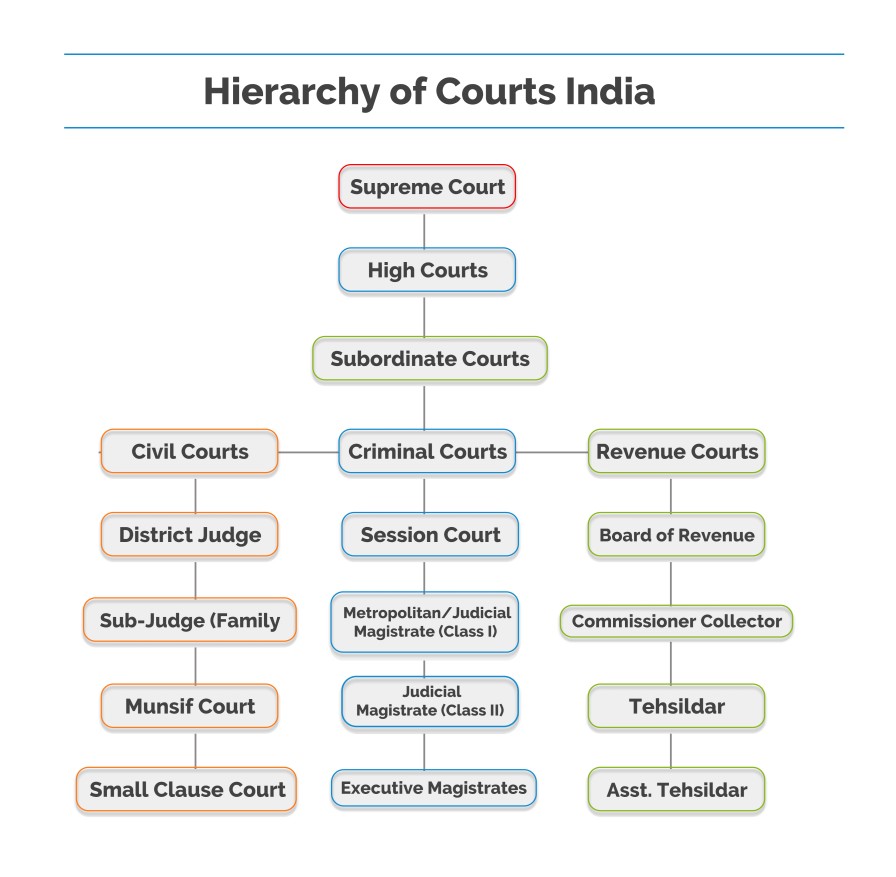

The Indian federal system is based on dual division of power, however, the Indian Judiciary is integrated and there is only one judicial system that follows a hierarchy. Part V under chapter IV (The Union Judiciary) and Part VI under chapter VI (Subordinate Courts) of the constitution enumerates provisions for the Judiciary. The Supreme Court is the apex court of judicial functions, below which lies the High Court, and at the bottom of the hierarchy come subordinate courts.

History of Indian Judiciary

The Indian Judiciary was adopted as an extension of the British Legal System. The earliest instance of judicial proceeding was bought by the Royal Charter of Charles II in 1661 that gave the governor, powers to adjudicate on civil and criminal matters according to the laws of England. Thereafter, King George I in 1726, established the Mayor’s Courts in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta. However, the Regulating Act of 1773, established the first Supreme Court of India in Calcutta, which was also later established in Madras and Bombay.

Subsequently, High courts were established through the High Courts Act of 1861. During this time, however, the highest court of appeal was the Privy Council. Lastly, the Government of India Act, 1935, established the Federal Court of India to act as a court of appeal between High Courts and Privy Council. The Federal Court continued the function even after independence until 26th January 1950, when thereon, Supreme Court, based in Delhi became the highest court of appeal.

Structure of Judiciary & Hierarchy of Courts in India

The Indian Judiciary has a unified structure, the lowest and foremost court of law is the lower court, after which appeals can be made in the higher courts (High Court and Supreme Court). The jurisdiction of a particular court can be decided on 3 bases: Pecuniary, territorial, and Subjectorial. The following points denote the structure and Hierarchy of Courts in India.

- Supreme Court (Highest Court of Appeal)

- High Courts( In States and UTs)

- Lower/Subordinate courts in districts (District and Sessions Courts)

- Subordinate Judges’ Court (Civil), Metropolitan Magistrate

- Court of Sessions(Criminal)

- Subordinate Magistrates’ Courts

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the apex court of the country. It consists of a Chief Justice and 30 other judges. The Chief Justice of India is appointed by the President and all other judges are appointed by the President after consulting various other judges of supreme courts and high courts. Article 124 of the constitution talks about the establishment and constitution of the Supreme Court. Once appointed the judges can hold office until the age of 65.

Under Article 129, Supreme Court is declared as a Court of record with the power to punish for contempt of itself. Under Article 137, it has the power to review a judgment pronounced or order made by itself (curative petition).

Original Jurisdiction:

Article 131 lays down the original jurisdiction of Supreme Court, under which, the Supreme Court has authority to decide disputes between the Government of India and one or more states, between two or more states, between Government of India and State(s) on one side and State(s) on the other side. The proviso of this Article excludes any treaty, agreement, covenant etc.

Writ Jurisdiction:

Article 32 of the constitution guarantees constitutional remedies in the form of writs. These writs are mandamus, prohibition, certiorari, habeas corpus, and quo warranto.

Habeas Corpus means, ‘have the body’, if an individual has been wrongly detained, his representatives can move to the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the High Court under Article 226, to demand his release.

Mandamus means ‘we command’, it is a judicial order to a constitutional, statutory or non-statutory body asking to carry out a public duty imposed by law or to refrain from doing a particular act, that does not fall under their authority.

Prohibition literally means to ‘prohibit’, this is a judicial order issued by the High Court or Supreme Court to an inferior court or quasi-judicial body forbidding the latter to continue proceedings therein in excess of its jurisdiction.

Certiorari means to certify, this is a judicial order that can be issued by the Supreme Court or High Court to any quasi-judicial or administrative body to transmit to the court, records of proceedings pending therein for scrutiny, and decide the legality of orders passed by them.

Lastly, Quo Warranto means what is your authority, it is a judicial order asking a person, who occupies the public office, to show by what authority she holds the office.

Appellate Jurisdiction:

Supreme Court is the highest court of appeal. It can entertain any criminal or civil matter passed on as an appeal from the High Court.

Advisory Jurisdiction:

The Supreme Court can advise the President on any question of law or fact of public importance, or cases belonging to disputes arising out of pre-constitution treaties and agreements which are excluded from its original jurisdiction.

Review Jurisdiction:

Supreme Court can review its own orders or judgments, subject to any law made by the parliament.

High Courts

The High Court is the only court apart from Supreme Court, vested with the power to review the constitution. The High Courts are consist of a Chief Justice and other judges appointed by the President of India. A judge of the High Court holds office up until the age of 62. The High Court, under Article 227 has the power of superintendence over all courts and tribunals except those of Armed Forces. This also includes revisional powers in case of any gross violation of rights or abuse of jurisdiction.

Under Article 228, if the High Court is satisfied that a pending case before a subordinate court has a substantial question of law, it can transfer the case to itself.

Appellate Jurisdiction:

Extends to both civil and criminal matters. In the case of civil matters, a High Court appeal is either a second or first appeal. In criminal cases, jurisdiction extends to cases tried by Sessions and Additional Sessions Judges.

Writ Jurisdiction:

Under Article 226, the High Courts have a wider writ jurisdiction than the Supreme Court, since it can issue writ not only on the violation of a fundamental right but also on the violation of any other right (ex: legal right).

Original Jurisdiction:

The Original Jurisdiction of High Courts Includes enforcement of fundamental rights, issuing rights to any person or government, and settlement of disputes relating to election to the Union and State Legislatures and jurisdiction over revenue matters.

Subordinate Courts

Courts that are subordinate to the High Court are called subordinate courts. Every district has a district court, with appellate jurisdiction. Moreover, each district also has some lower, subordinate courts that are under the administrative control of the High Court. These are:

- Civil Courts

- Criminal Courts

- Revenue Courts

Civil Courts

Article 233 of the Constitution lays down the appointment of district judges that shall be done by the Governor of that State in consultation with the High Court. The court of district judge is the highest civil court in a district, it exercises judicial, administrative powers, and has both appellate and original jurisdiction. Below the district judge are sub-judge, additional sub-judge, and munsif courts which are located in sub-divisional and district headquarters.

Civil cases are filed in the munsif’s court and can be appealed to the sub-judge or additional sub-judge, further appeal lies with the district judge. Section 9 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 states the jurisdiction of these courts, which is to try any civil matter except suits of which their cognizance is either expressly or impliedly barred.

Separate family courts, equal to sub judge are established in the districts to hear family matters, like divorce etc.

Criminal Courts

Section 6 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 states that there shall be four classes of criminal courts: Court of Session, Judicial Magistrate First Class, Judicial Magistrate Second Class, Executive Magistrate.

Court of Session

Under Section 7 of CrPC, every State shall have session divisions, the number of which will be decided by the State Government on the advice of High Courts. Section 9, further states that every Session will have a Court of Sessions, to be presided over by a Judge appointed by the High Court. Additional Sessions Judge and Assistant Sessions Judge can also be appointed by the High Court.

The Court of Sessions can try any criminal matter under the Indian Penal Code, however when it comes to punishment, the Session Judge and Additional Session Judge can pass any sentence authorized by law, but in case of the death penalty, it has to be confirmed by the High Court. The Assistant Session Judge can pass any order except the death penalty or imprisonment of life.

Court of Metropolitan Magistrate

The areas with a population of more than a million are metropolitan areas. The State Government in consultation with the High Court can establish as many Metropolitan Courts in the area as it deems fit. The High Court appoints a Chief Metropolitan Magistrate (CMM) for a particular area. An additional CMM can also be appointed. The CMM and Additional CMM are subordinate to the Sessions Judge. CMM can pass any sentence authorized by law, except the death penalty or life imprisonment or imprisonment for a term exceeding seven years.

Court of Judicial Magistrate

Every state is divided into Sessions and the State Government in consultation with the High Court can establish as many courts of Judicial Magistrate of first-class and second-class as it may deem fit. In every district, a Judicial Magistrate of first-class (JMFC) will be appointed as Cheif Judicial Magistrate (CJM). The High Court may also appoint a Judicial Magistrate of first-class as an Additional Cheif Judicial Magistrate (ACJM). CJM will be subordinate to the Sessions Judge and may pass any sentence authorized by law, apart from the death penalty, life imprisonment and imprisonment for a term exceeding seven years.

Court of Executive Magistrate

The State Government in every district and metropolitan area can appoint as many Executive Magistrates as it may deem fit. One of them shall be District Magistrate (DM), another Additional District Magistrate (ADM) can be appointed. The Executive Magistrates shall look into administrative and executive cases.

Revenue Courts

On the top of the hierarchy of revenue, matters are the board of revenue, under which comes Commissioner Collector, and at the bottom of the hierarchy lies Tehsildar (Assistant Tehsildar could also be present)

Conclusion

The above-explained hierarchy is followed in the Indian Judicial System. Apart from Supreme Court, High Court, and Subordinate Courts, Tribunals are another form of justice rendering institutions, however, these are not ‘courts’ per se, and have specific, predefined jurisdiction. Tribunals hold jurisdiction in administrative and service matters. Therefore, there are separate Administrative Tribunals. The subject matter of tribunals includes recruitment of persons appointed to public services in Union, State and Local Authorities, or any corporation owned and controlled by the Government. Moreover, they may deal in matters of taxes, foreign exchange, labor disputes, land reforms, the ceiling of urban property, rent and tenancy issues, etc.

This article has been written by Vanshika Arora, B.A. LL.B student at Army Institute of Law, Mohali.